Underthink

What luck for leaders that men do not think. —Adolf Hitler

I.

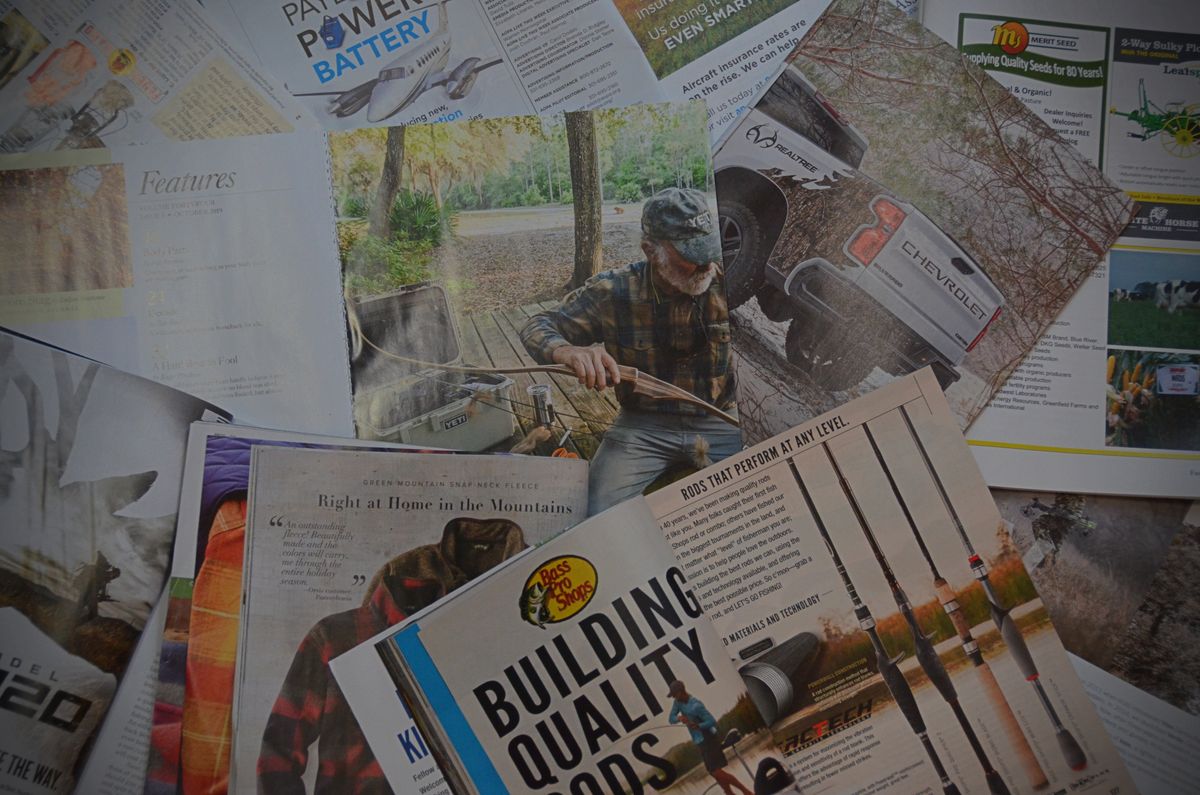

I can’t help it. I wish the box in the picture was mine. It sits on the moldering deck with a shimmering luster, lid flung open, a veritable cornucopia of archery accessories. Bow square, scissors, an old broadhead case, some dental floss for emergency serving, a Sharpie for numbering arrows. A shooting glove rests atop a Ziploc bag that holds fletching for arrows. Muskrat fur string silencers lie in front of this archery tool-box.

Midmorning light cuts a swath on the far side of the palmetto bush, falling white on the scrub trees of what could be somewhere in Florida. A yellow lab sleeps off the nights chill in the sun, while nearer on the edge of the aging cabin porch a man in a flannel shirt sits and prepares to string his recurve bow. The bow is a piece of functional art—mahogany laminated with a lighter wood, hickory or teak perhaps. A stainless vacuum mug sits behind him with the liquid complement to an easy day.

I always wanted to be a traditional archer, but I like that toolbox. Maybe I’ll start my traditional gear with the box or the mug. Folks, meet Flip Pallot, Yeti ambassador. A Yeti is not a sasquatch, but they are built for the wild.

Begrudgingly, I admit this advertisement is a piece of excellence. It feels like you or I could be in the picture, what with the Ziploc bags and dental floss and the old porch and Sharpies, these being common elements in our lives. However, a few factors are mere wishes for the average sportsman—the expensive bow, the fact that it appears to be midmorning when all the rest of us hard-bitten men are working, and the impression that it is someplace where palmettos grow. The picture has a feel of accessibility with just enough horizon in it to make us hungry. The Yeti Gobox is sold at the hardware store, so it is within reach, even if not within the budget.

Whether that’s what the marketing agency wanted me to feel I can’t tell, but that’s what I felt after I stared at the advertisement long enough. I assume they wanted me to think that I, too, should have a Yeti Loadout GoBox, and I would have if I had not been on my guard. Whoever markets Yeti has done an admirable job of turning a box into a status symbol—the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. And there is another factor—style value. We can wear a hat with the name of a cooler on it with pride. “What’s in a name?” is the famous Shakespearean quotation. In this case, a bit of pride for the consumer and a mound of moolah for the manufacturer. At one point a fishing guide told me he takes his Yeti cooler home each evening. “The most widely stolen thing,” he said. “People love ‘em.” He left his $2,500 fish-finder on his boat.

An ancient philosopher, Aristotle, said “The emotions are all those feelings that change men, so as to affect their judgment.” This kind of appeal to emotions to sell is what the selfsame Aristotle would have called false pathos, or manipulation of human emotions for selfish ends, stirring up emotion at the sight of an advertisement so that emotions override good sense. But who cares about some ancient philosopher’s version of ethics when you can excavate human emotion to line your wallet?

II.

"Guess what?” my brother says. “I found some gluten-free apples the other day at the grocery store. Said it right on the bag.”

I raise my eyebrow.

He eyes me askance, seeing a lack of the incredulous expression. “Apples are naturally gluten-free. Gluten is found only in grains.”

Oh! I thought that perhaps by some chemical or scientific wizardry they had purged the gluten from an apple.

“Oh no,” he says, “The day we have gluten in apples we do have a problem.”

The marketing logic goes like this: we all have heard of gluten intolerance, which is bad. We should eat less gluten. When we see a bag of apples with no gluten, we draw a shaky, subconscious connection between “bad” gluten and “good” gluten-free, and we buy the apples. Victory for the marketing company, and they have hoodwinked the consumer by hollering a non sequitur, “Have an apple because Isaac Newton watched one fall from a tree.” That might sell more apples, come to think of it.

III.

I walk into the hardware store. I need a bucket—just a basic plastic bucket. Here is one priced at five dollars. A useful item for once.

Here’s another, but it costs forty dollars. It’s an “impact resistant” bucket, but it also has a Very Special Brand Name on it, which I’m guessing accounts for about thirty dollars of the price. What’s an impact resistant bucket that makes it worth thirty extra dollars?

All buckets are impact resistant, as long as the force of molecular attraction remains—or if what they taught me in seventh grade science still holds out. One might be more impact resistant, but here is the marketing tightrope: claim too much, and the company will be liable if it breaks; claim not enough and the bucket will have to stand on its own merits. Horrors! Again, the ill-traceable connection playing on the subconsciousness of the passive consumer—buy the better bucket with a household name; never mind the fact that we could buy eight of the less-impact-resistant buckets for the same damage.

IV.

Sin is very convenient now. If you happen to be Catholic, you can download an app to repent of your sins. You will have your own sinner’s profile, and you can easily select which category of indiscretion you have committed, how many days it was since your last confession (to see if you are slacking), and send your order ahead to the priest, the same way you can order your chicken strips from the chain restaurant. Maybe now we can swing by the priest to get absolution on Saturday errands. Bank, hardware, auto parts, priest. Perhaps we can even pay penance with Paypal.

V.

For $99.99, you can have your own quart of souvenir Rocky Mountain Air, without the struggle or fear of hypoxia. It is bottled at 14,000 feet above sea level, a Colorado mountaintop experience delivered to your doorstep via mason jar. You’ll find it on eBay. It’s as light and fresh as the emperor’s clothes. Free shipping. Better hurry, there are only two left.

VI.

These schemes whereby we fall from reason to snatch up the latest are simple enough to be embarrassing and—to anyone who bothers thinking about it— intellectually repulsive. Combine a greedy, unscrupulous merchant and people who feel more strongly than they think, and the product is thoughtless consumerism. I’m not against emotions, but the masterminds are juking the feely buttons and we are letting them play into our sense of ego, style, and the notion that we are only two steps away from Caught Up. We like to think we are in the parade, but instead, we are caught in the stampede.

A predatory-prey awareness would serve us well whenever we venture out into the cold, dark world of sales. Tread lightly, look sharp, and be quick to run. I like to sneak into a store that holds many things of interest, look and wish for things, admire the cunning of how they hang all the expensive products at eye level and arrange them artsy-like, and after thinking I cannot do without a particular shiny object for even one more day, I turn and nonchalantly walk out unscathed. I have beat the system, and I feel swell. It’s an exercise in personal discipline, and I recommend it. But sheer avoidance is hardly the cure. It’s a beginning that sets the stage for insight, but it is only a version of hands-off circumvention. We need a scalpel of honest thought to perform surgery on this chicanery.

Do we care that we are being manipulated in the marketplaces? Like some Pavlovian dog, slobbering at the jingling of a bell even without getting the substance?

The subject gets heavier as we go along. Perhaps there are some amoral things, but there are none neutral. Our compromise of value begins with the inconsequential and leaches through to ideas, concepts, and religions. We fall for these products for their convenience, or because we forget to take little things seriously, and set up a lifestyle of washing downstream like flotsam. Our swords fall from our hands as we sleep in the sun.

When Hitler brainwashed the Germans into Nazism, he pushed his agenda with several tools, two of them being careful selection of media and emotional rhetoric. Hitler himself said that the written word lent itself to too much introspection and that he preferred public speaking because it held more power to sway the masses. People swooned when he spoke, and his program became so powerful that few Christians—who were happily living affluent lives—had the capacity of critical thought to see through his reasoning, and they compromised without a whimper.

What if this this media brainwashing problem is here again, maybe not with herd-poisoning and Hitlerian rhetoric, but in a visual, persuasion-by-emotion way that conditions us to need what the marketeers want to sell? Perhaps in a Huxleyan, Brave-New-World sort of way, where our information is not withheld, and we are not directly lied to, only the truth is diluted and taken out of context—our apples are gluten-free. Both tactics strike at the same object; we are never sure if the facts are factual, but we nevertheless plant our feet in midair on the basis of our perception. A man can underthink and unwittingly compromise without visible repercussion.

Our battle hymn fades to a lullaby. Hedonism lurks behind the American Dream—the pleasure of plenty, the assurance of insurance, the sweetness of going with the flow. And our eyes are closing, closing; they are dim; we have no reason to fight or think: only dream. Sweet, sweet sleep…